Analysis

Nuclear power is in global decline – minus 18 percent over the last 20 years – but the Russian state-owned nuclear entity Rosatom sees this as an opportunity and sets itself up to become a global leader.

Rosatom is one of Russia’s largest and most powerful energy companies and silent when it comes to international attention. Now, Rosatom is on its way to becoming the most powerful nuclear company in the world. Rosatom has done a lot in silence to boost itself up, and there are three reasons why its future looks prosperous.

- The Russian export-oriented oil and gas sector struggles, due to low oil prices and stiff competition in the gas sector. As a result, the nuclear power sector is forced to compensate for those losses.

- Nuclear power is on the decline worldwide and especially in developing world. Rosatom is keen to fill the gap that is left by leading technology companies.

- Rosatom is likely to experience two breakthroughs in its technological development over the coming two years that could put the company ahead of its global competition. The company claims to have developed the safest nuclear fuel, and has commissioned the world’s first Floating Nuclear Power Plant (FNPP).

Both of these reasons represent certainly major opportunities for Rosatom, however they also pose a severe financial risk for the company and the Russian state.

Russia’s declining role in the oil and gas sector

Russian financial and political stability largely relies on the revenues generated by the export-oriented oil and gas sector. Over the last five years, however, Russian state-controlled oil and gas companies have lost the ability to receive those high export revenues. Russia is highly dependent on those export revenues in order to maintain a balanced state-budget, thus ultimately necessary for the ruling elites to remain in power.

Since 2014 the global oil price has declined and appears to have stabilized at a relatively low level, despite several attempts in cooperation with OPEC, to influence the global oil market and the oil-price level. The low oil price has resulted in lower revenues, as exports are already closer to maximum capacities most of the time. Rosatom’s export strategy likely includes several possible sources of income, ideally a combination of construction, service, operation, and fuel supply, which makes it less vulnerable to price fluctuations.

The Russian gas export sector faces similar difficult challenges. Although the contribution of export revenues to the state budget are lower than those of the oil sector it is still critical. Furthermore, Russia’s state-owned gas company Gazprom is an essential asset for the Russian state. Amongst others, Gazprom’s international outreach has helped Russian foreign economic and political interests. As a state-owned company, Rosatom’s international outreach could also serve as a political tool to influence bilateral relations. Having control over another country’s electricity production, such as Iran and possibly the EU member Hungary in the future, or maybe even access over the entire nuclear sector is a foreign political asset and serves great diplomatic influence.

International sanctions on Russia are partially imposed on the Russian oil and gas sector. This deprives the entire industry from investments, partnerships, and access to technologies. This makes it almost impossible for Russian companies to stay competitive in advanced areas such as offshore drilling and Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) production. Currently, there are no political sanctions imposed on Rosatom. The situation could change, however, especially if the company gains more influence. Those chances of foreign sanctions nevertheless decrease with Rosatom’s increasing number of foreign projects.

There are also risks involved in Rosatom’s compensation strategy. There is no evidence that nuclear export could replace the large oil and gas revenues and thus the nuclear foreign expansion might only serve as an additional source of income. While on the one side, it might be a financial advantage, once agreed on the construction of an NPP, as investments will flow right in the beginning, there is on the other side, a lower certainty for high future revenues, although Rosatom most likely remains the single fuel supplier for its constructed NPPs. The key financial question for Rosatom remains how stable the economies of the host countries in the future will be.

Rosatom hopes to fill the nuclear gap

Since the Fukushima reactor accident of 2011, the global nuclear energy leaders Japan and France downsized their nuclear sector dramatically. Germany even decided to phase-out its nuclear reactors. Leading technology companies have left the international scene, leaving an opening for Rosatom to fill.

As previously stated, the Russian state has an interest in Rosatom’s foreign expansion and now there is a perceived opportunity. Rosatom benefits from Russia’s decisive support. While nuclear downsizing takes place in industrialized nations, the nuclear sector in Russia is in the process of modernization. The Russian nuclear sector is well advanced compared to other Western nations, and as a member of the Nuclear Supplier Group (NSG), Russia has acknowledged rights to export nuclear technology and fuels; this status owed to the former Soviet Union’s nuclear priority. Up until 2030, Rosatom plans to build five new NPPs in Russia, where it already operates ten NPPs.

Rosatom’s strategic importance is, why its foreign expansion is booming: The company has several NPP projects of different scale abroad, which according to the company, has meant more than $130 billion of investments until 2030. Rosatom currently holds 67 percent of the global NPP construction market. Every single project is special and prestigious for Russia because they are grounded on proceeding bilateral political partnerships. Many projects are backed by government-to-government loans so that the Russian state takes over the financial risks and enables Rosatom to underbid other nuclear firms for foreign projects.

Russia’s strategy is to build a foothold in less developed countries with emerging economies. Rosatom’s first and only three operable NPPs abroad are in China, Iran, and India. While it still took Rosatom a long time and effort to construct the Iranian Busher NPP, the Indian Kudankulam NPP and the Chinese Tianwan NPP represent rather successful models of foreign projects. In all three countries, Rosatom plans to build two more NPPs. Russia is also building Bangladesh’s first NPP and is planning to build its first NPP in Egypt. Also, in the former Soviet-Union, Rosatom has two NPPs projects. One in Belarus and another in Uzbekistan.

The contracts between Rosatom and the partner country’s companies or agencies are in most cases, buoyed by governmental agreements. The range of Rosatom’s involvement and continuation contracts are different from each project. While the Tianwan project in China is a rather joint project between Rosatom and China’s National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC), the NPP project in Egypt will be completely run by Rosatom, including future fuel supplies, and training- and technology support.

Politically strategically and economically important for Russia, is Rosatom’s nuclear outreach to the West. Next to the NATO-member Turkey, where Rosatom launched a large NPP project in Akkuyu, Finland and EU-member Hungary also tasked Rosatom with the construction of one NPP each.

All the mentioned projects are at least already approved if not under construction or already operational. Rosatom, however, looks further in the future and plans with reasonable optimism to build NPPs in Saudi-Arabia and the Czech Republic. Both projects would boost Rosatom’s prestige and Russia’s foreign leverage to another level. With an NPP project in Saudi Arabia, Russia could enhance its foothold in the Middle East. If Russia were to obtain a second NPP within the EU, the (Western-) European pursued nuclear downsize would experience a setback with the consequence that the EU’s internal political division could deepen, with pro-Russian fractions filling the void.

The way ahead

The future looks bright for Rosatom, but there are at least three reasons that put the story of success at risk. First, Rosatom’s order book is full and the company has secured projects for the coming decade and still continues to plan new projects, as in Saudi-Arabia, and the Czech Republic. However, simultaneous high-cost construction efforts might bring the company to a financial and capacity risk, where contracts could be delayed or go unfulfilled.

Second, Rosatom’s success occurs in developing countries and raises concerns over financing these projects. While the company is not really transparent in this regard, it is likely that most of the investments are bailed by the Russian state and Rosatom itself. Whether or not the project will return its investment is dependent on several factors, including long term economic prospects, and political stability. While Rosatom’s presence in China and India are probably financially secured, the question of Bangladesh’, Belarus’ and Uzbekistan’s future prospects are more uncertain. This is also why Rosatom is keen to secure projects in Hungary, Finland and potentially in the Czech Republic.

Third, Rosatom likely takes investment risks in countries where the Russian foothold is strong, although this strategy could backfire. Russia’s closest ally is Belarus, all other countries are either politically independent or possess a non-Russian bloc status. What Rosatom needs for its projects is political stability and those countries to maintain good relations with Russia over a longer term. In 2015, this occurred with Rosatom’s NPP project in Turkey. Bilateral relations were at a low after a Russian fighter had been shot down by Turkey. The NPP project, and a Russian-Turkish gas pipeline project were suspended. Once diplomacy stabilized bilateral relations, Rosatom’s eventually started construction on the Turkish NPP in 2018.

The experience of the Iranian Busher-NPP has demonstrated Rosatom’s exposure to financial, economic and political risks. The Busher-NPP was Rosatom’s first foreign project. The company endured due to unskilled engineers which delayed construction schedules resulting in cost tripling over a 12 years construction time. Simultaneously, Rosatom struggled over international pressure put on Russia, over Western concerns of Iranian nuclear weapons ambitions. This further contributed to the delayed construction timelines. The eventually successful completion of Busher, however, serves Rosatom as a role-model for its foreign expansion, and less as a repercussion. Despite the drawbacks of the Busher-NPP, Rosatom has proven as a reliable partner for foreign partners and simultaneously kept the Russian nuclear expertise competitive after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which made further foreign projects possible. Successful completion demonstrated to Rosatom’s potential customers, that Russia is capable and committed despite Western pressure.

Accident tolerant fuels

Rosatom announced in 2018 that the subsidiary fuel company, “TVEL”, had developed an accident-tolerant nuclear fuel. This fuel is designed to reduce the amount of hydrogen generated in case of a reactor meltdown while preventing an explosion of the nuclear reactor as it happened in the 2011 Fukushima accident.

According to TVEL, the fuel will be tested in 2019 and introduced by 2020-21. Several fuel-provider world-wide are working on the development of similar accident-tolerant fuels. However, Rosatom’s subsidiary seems to be two to three years ahead. Competing French, U.S., and Japanese nuclear companies do not expect to commercialize their fuels before 2023. With this, Rosatom would improve its status as a leading nuclear fuel-provider, to one part because of Rosatom’s worldwide largest nuclear fuel reserves, to the other part because of the fuel’s special safety feature. The company hopes that it can further improve its status as a global competitor and enter markets where safety standards have a priority, such as the EU.

Floating Nuclear Power Plant “Akademik Lomonossov”

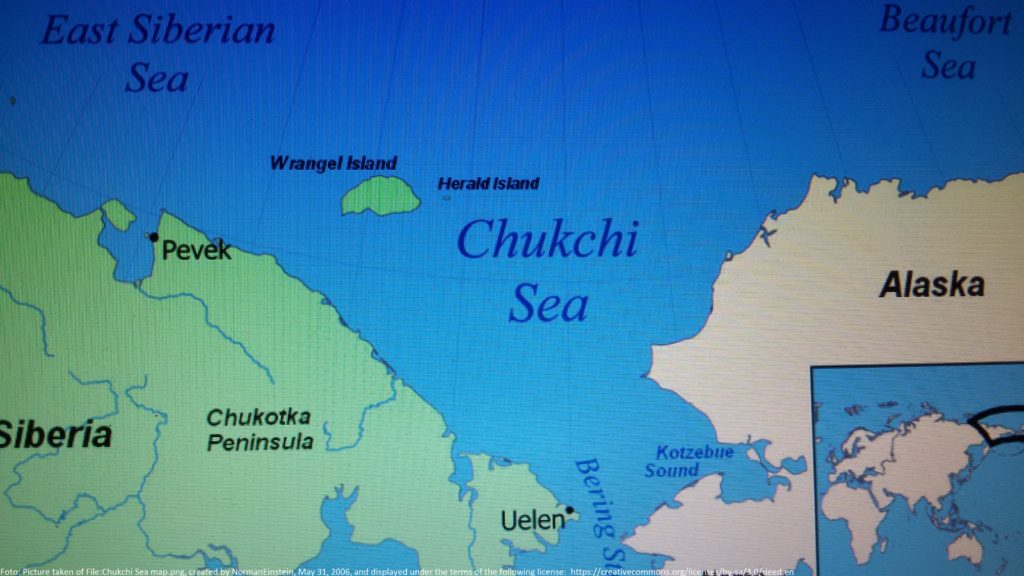

In 2018, Rosatom began the final test-phase of the “Akademik Lomonossov”, the world’s first Floating Nuclear Power Plant (FNPP). The FNPP is fixed on a swimming platform with two reactors. Once operational, it is able to produce 70 megawatts, enough to supply a population of 70,000 people. After the test trials are completed in March 2019, the intent is to transfer the FNPP to the Russian city of Pevek, in the Russian Arctic region. The FNPP will supply the city with electricity and will probably assist the Russian oil and gas industry to explore the Arctic region offshore.

According to Rosatom, the reactors have a 35-40-year lifetime, which can be extended for an additional 50 years. The company also plans to construct a second and improved FNPP with an unknown completion date.

While it took Rosatom about twelve years, and cost approximately $400 million to develop the Akademik Lomonossov, it has become a prestigious showpiece for Russia. Its importance is twofold.

First, Rosatom’s strategy of FNPPs is its export potential. With sea trials ongoing, and the number of unique capabilities the FNPP could have remained uncertain, the mobility and flexibility could be advantageous for customers in remote or hazardous areas. In this case, Rosatom’s business plan probably will likely include the rent or sale of FNPPs, or its electricity, wherever the FNPP will be deployed. Also, the lower amount of produced electricity by the FNPP presents an opportunity for small scale consumers to save costs. Rosatom also provides a viable security plan: as the FNPP is seagoing, there will always be enough cooling water. Objections, however, against the security plan remain an obstacle.

Second, FNPPs have a high potential to be used in the Russian Arctic or the Far East. For more than a decade, Russia has strategized the exploration of the Arctic. The Akademik Lomonossov might be a pilot project for the nuclearization of the Arctic, but it puts Russia again ahead of its global competition for the Arctic. Russia already controls Arctic shipping routes along the Eurasian continent and holds an established and permanent military presence. Russia is also most advanced in securing legal rights for resource extraction in the Arctic.

While there are several advantages regarding the FNPPs capabilities, lack of evidence supports these claims. Objections against the safety of nuclear reactors remain. Given the inglorious reputation of Russian nuclear fleets, guarantees of whether FNPPs can deliver maximum security in case of accidents is questionable. For an FNPP in a more isolated environment or at sea, can be seen as an advantage in case of a serious accident, however, those conditions might increase of accidents. Along with the safety of nuclear reactors, there is a question of feasibility for such a project. There are interests of other nuclear competitors to develop similar FNPPs, but whether there is sufficient global demand, making those investments viable remains unanswered.

Russia has a distinct advantage. The FNPP serves three of Russia’s political objectives. It serves the prestige for Moscow, it supports Rosatom’s foreign expansionary objectives and enables Russia’s to be first in the Arctic.

Future prospects

Rosatom’s future appears to be optimistic. Moscow’s massive support and investment diminish all risks. The focus on the domestic and the foreign markets of the company, including an all-combined offer to customers, of construction, service, maintenance, technology transfer, and fuel supply appears to be an export model that has advantages over the volatile oil and gas export model. Finally, Moscow’s unyielding support when facing Western or other international objections promises a positive outlook for Rosatom.